How eScan Antivirus Delivered Malware Instead of Protection

Want to learn ethical hacking? I built a complete course. Have a look!

Learn penetration testing, web exploitation, network security, and the hacker mindset:

→ Master ethical hacking hands-on

(The link supports me directly as your instructor!)

Hacking is not a hobby but a way of life!

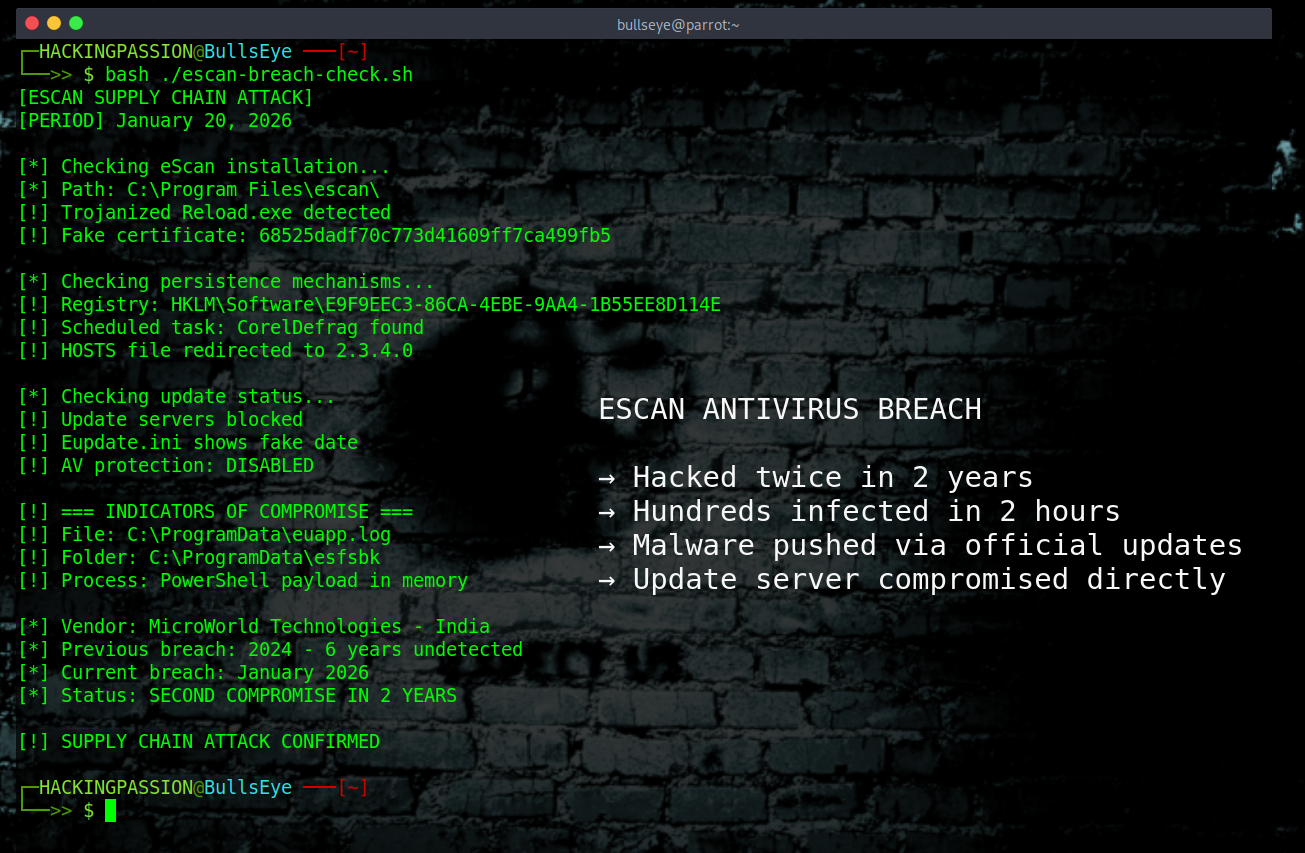

eScan antivirus got hacked. Again. Same company, same update infrastructure exploited, two years apart. This time: hundreds of machines infected in a 2-hour window.

New findings dropped this week. Researchers confirmed the scope of the damage across South Asia. The vendor is now threatening legal action against the security firm that reported it. Two weeks after the attack, we now have the full picture of what went wrong.

On January 20, 2026, eScan pushed a software update to customers. Nothing unusual, antivirus products update all the time. Except this update contained malware. It came through the official update channel, carried what looked like a legitimate digital signature, and installed itself with full system privileges. That is exactly how antivirus software is supposed to work, which made it the perfect delivery mechanism.

The first time this happened was in 2024. Security researchers Jan Rubín and Milánek discovered that attackers linked to North Korea’s Kimsuky APT group had been exploiting a vulnerability in eScan’s update mechanism since 2018. Six years. eScan is made by MicroWorld Technologies, an Indian cybersecurity company. The problem was embarrassingly simple: they were downloading updates over HTTP instead of HTTPS. No encryption meant attackers could intercept the connection and swap the legitimate update for malware. The researchers reported it, eScan fixed it in July 2023, and everyone moved on.

Except the attackers came back.

This time they did not need a man-in-the-middle attack. They got directly into eScan’s regional update server. How they got access is still unknown. What we know is that they replaced a legitimate file called Reload.exe with a trojanized version, and eScan’s own update system pushed it to customers.

The malware is sophisticated and shows the attackers understood eScan’s internals deeply.

Stage 1 starts with the trojanized Reload.exe:

- → Normal location:

C:\Program Files (x86)\escan\reload.exe - → Gets launched by other eScan components at runtime

- → Attackers replaced it with heavily obfuscated version

- → Uses constant unfolding and indirect branching to make reverse engineering difficult

- → Carries fake digital signature with certificate serial number

68525dadf70c773d41609ff7ca499fb5 - → Looks signed, but signature is invalid

When Reload.exe runs:

- → Initializes .NET Common Language Runtime inside its own process

- → Loads small executable in memory

- → This executable is modified version of UnmanagedPowerShell

- → Lets attackers run PowerShell code inside any process without launching powershell.exe

- → Malicious scripts never get flagged

The implant then executes three separate Base64-encoded PowerShell payloads, each with a specific job.

The first payload tampers with eScan itself. It deletes critical eScan files, including the Remote Support Utility, and modifies registry keys to add the entire Windows and Program Files directories to the antivirus exception list. That means the antivirus will ignore anything running from those locations, which is basically everything.

Then it does something clever. It edits the Windows HOSTS file to redirect eScan’s update servers to IP address 2.3.4.0, which leads nowhere. The antivirus tries to check for updates, the connection fails silently, and the user never knows anything is wrong.

Payload 2 handles the AMSI bypass:

- → Finds the address of

AmsiScanBufferfunction - → Patches it to always return an error

- → Disables Windows Defender’s ability to scan scripts in memory

Payload 3 validates whether the victim should receive the final infection. It checks installed software, running processes, and services against a blocklist of security tools and analysis software:

- → Various antivirus products

- → Wireshark

- → WinDbg

- → TCPView

- → Process Explorer

- → Process Monitor

- → OllyDbg

- → Other security and forensic tools

If any of these are found, the infection stops. Standard sandbox and researcher evasion, but it also means users with these tools were accidentally protected.

If validation passes, the payload deploys two persistence mechanisms:

- → Writes encrypted PowerShell payload to registry key

HKLM\Software\E9F9EEC3-86CA-4EBE-9AA4-1B55EE8D114Eunder value named Corel - → Creates scheduled task

Microsoft\Windows\Defrag\CorelDefragthat runs daily at random time - → Task reads payload from registry, Base64-decodes it, executes it

- → Replaces

C:\Program Files (x86)\eScan\CONSCTLX.exewith malicious 64-bit downloader

CONSCTLX.exe is obfuscated the same way as Reload.exe. What it does:

- → Writes current date to

C:\Program Files (x86)\eScan\Eupdate.ini - → This file controls what eScan interface displays as last update time

- → User sees recent date and thinks everything is working

- → Antivirus is actually disabled and cannot receive real updates

- → Retrieves PowerShell payload from registry and executes it

- → Provides backup persistence path if scheduled task gets deleted

- → Can fetch additional shellcode from fallback C2 servers

- → Decrypts response with RC4 before execution

The final PowerShell payload:

- → Performs same validation checks again

- → Sends system information to command servers

- → Data includes victim ID, username, current process name

- → Encrypted with RC4 and Base64-encoded in a cookie

- → C2 server can respond with additional PowerShell scripts to execute

Researchers identified hundreds of infected machines, mostly in South Asia. India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and the Philippines were hit hardest. Both home users and organizations were affected.

The command and control infrastructure uses multiple domains and a direct IP:

- →

hxxps[://]vhs[.]delrosal[.]net/i - →

hxxps[://]tumama[.]hns[.]to - →

hxxps[://]blackice[.]sol-domain[.]org - →

hxxps[://]codegiant[.]io/dd/dd/dd[.]git/download/main/middleware[.]ts - →

504e1a42.host.njalla[.]net - →

185.241.208[.]115 - →

hxxps[://]csc[.]biologii[.]net/sooc(fallback) - →

hxxps[://]airanks[.]hns[.]to(fallback)

The backdoor can receive additional PowerShell scripts from the C2 servers and execute them. This means the attackers could deploy anything they want on infected systems: ransomware, cryptominers, data stealers, or just sit quietly and wait.

Now here is where it gets interesting.

A security research firm detected the attack on January 20 and contacted eScan. eScan claims they detected it themselves through internal monitoring, isolated the affected infrastructure within an hour, and took the global update system offline for over eight hours. They released a security advisory on January 22 and a patch to fix compromised systems.

But now the researchers and eScan are publicly fighting about the details. eScan called the research report inaccurate and asked them to remove their social media posts. eScan says this was not a supply chain attack, just unauthorized access to a regional server. The researchers deleted their social posts but kept their technical blog online. eScan is working with lawyers.

The disagreement does not change what happened. Customers trusted their antivirus to protect them, and instead it delivered malware. Whether you call it a supply chain attack or unauthorized infrastructure access, the result is the same.

In cybersecurity, attribution is one of the hardest problems. IP addresses can be spoofed. Tools can be shared. Languages in code can be faked. What we know for sure is how the malware works, not necessarily who is behind it. The 2024 attack had links to North Korea’s Kimsuky group based on shared infrastructure and code similarities. The 2026 attack has no confirmed attribution yet. The tactics are similar, but that does not prove the same actors are responsible.

What we do know is that eScan’s update infrastructure has been compromised twice in two years. The first time exploited a six-year-old vulnerability. The second time exploited direct server access. Both times, the malware was designed to disable the antivirus and block automatic fixes.

If you run eScan, here is how to check for infection and what to do about it.

Indicators of compromise to check:

- → File:

C:\ProgramData\euapp.log(debug log created by malware) - → Folder:

C:\ProgramData\esfsbk(backup folder with ZIP files) - → Folder:

C:\ProgramData\efirst(marking indicator) - → Scheduled task:

Microsoft\Windows\Defrag\CorelDefrag - → Registry:

HKLM\Software\E9F9EEC3-86CA-4EBE-9AA4-1B55EE8D114Econtaining encoded PowerShell - → Registry:

HKLM\SOFTWARE\WOW6432Node\MicroWorld\eScan for Windows\ODSwith WTBases_new set to 999 - → HOSTS file: entries pointing eScan domains to

2.3.4.0 - → eScan showing recent update dates but not actually updating

What to do if you are affected:

The malware blocks automatic updates by modifying your HOSTS file and registry. This means you cannot fix this by simply clicking update in eScan. Manual intervention is required.

Step 1: Isolate the system from the network immediately. The backdoor can receive commands and download additional payloads.

Step 2: Check the HOSTS file at C:\Windows\System32\drivers\etc\hosts. Remove any entries that redirect eScan domains to 2.3.4.0 or any other IP.

Step 3: Open Task Scheduler and look under Microsoft\Windows\Defrag for any task named CorelDefrag or similar. Delete it.

Step 4: Open Registry Editor and delete the key HKLM\Software\E9F9EEC3-86CA-4EBE-9AA4-1B55EE8D114E if it exists.

Step 5: Check the eScan registry settings at HKLM\SOFTWARE\WOW6432Node\MicroWorld\eScan for Windows and restore normal values.

Step 6: Contact eScan directly at support@escanav.com or escanav.com/livechat to obtain the official remediation utility.

Step 7: Block the C2 domains and IP addresses listed above at your network perimeter.

Step 8: Reset credentials for any accounts accessed from the affected system and review eScan update logs for activity on January 20, 2026.

The broader lesson is uncomfortable but important. Antivirus software runs with the highest privileges on a system. If attackers can compromise the update mechanism, they can push malware to every customer at once, and it will be trusted and executed automatically. eScan got hit twice. The first attack ran for six years before discovery. The second lasted two hours. Progress, maybe. But a vendor breached twice in two years does not inspire confidence.

Understanding how supply chain attacks work and how to detect compromised systems is a core skill in modern security. I cover malware analysis, persistence mechanisms, and post-exploitation techniques in my ethical hacking course:

(The link supports me directly as your instructor!)

Hacking is not a hobby but a way of life.

Sources:

- → Morphisec Threat Bulletin - 2026 discovery

- → Avast GuptiMiner Research - 2024 discovery

→ Stay updated!

Get the latest posts in your inbox every week. Ethical hacking, security news, tutorials, and everything that catches my attention. If that sounds useful, drop your email below.